Kevin Sampsell | Longreads | August 2017 | 15 minutes (3,752 words)

Every time I talk to my mom on the phone, just as I’m getting ready to say goodbye, she slips in an abrupt update about her parents — my grandparents. Sometimes they’re in Switzerland. Sometimes they’re in Loma, Montana. Sometimes they’ve gotten “mixed up with bad people.” Sometimes they’ve completely disappeared or died mysteriously. Sometimes it sounds like a government conspiracy — a murder plot. At first, I didn’t know what to say in return. I’d ask how they died or what they were doing in Switzerland. In more recent conversations, I tried to place her back in reality. I’d say, “Mom, your parents have been dead for forty years.” I’d ask her how old they were and she would say 60, 70, or 75. She’s not sure. She says that all the time: I’m not sure. “How old are you?” I ask, and she laughs and says, “Oh, I think I’m about 25.” Once she said she was 18. She’s actually 88 years old.

For about two years now, my mother has been fighting with Alzheimer’s and the dementia that comes from that disease. She’s had years of struggle with diabetes and epilepsy — but her mental condition was always sharp. A lifelong democrat and the mother of six, Patsy loved sewing, making quilts, reading mystery novels, and watching Seattle Mariners baseball while enjoying a Pepsi (never Coke). I am her youngest son.

In 2015, she fell off a street curb and hit her head. She didn’t tell me about this until a week later. She prefaced the story of this accident by insisting that she was fine and only suffered some scrapes on her face and arm. I asked if she went to the hospital to make sure she didn’t break any bones or have a concussion. She said my brother, Mark, her main caregiver, took her to the emergency room but she left when they wanted to do some tests on her. She has long believed that doctors were just trying to take her money — which she has very little of anyway. I tried to chide her for not staying for the tests, for some kind of care, but she was stubborn and said it wasn’t necessary.

It wasn’t long after this that I noticed her becoming more forgetful, more confused, more dark. I began to suspect that she had Alzheimer’s or dementia and read that they are both often triggered by head injuries. Though we don’t live very far apart — her in Olympia, Washington and me 100 miles south, in Portland — I only get to see my mom a handful of times every year.

On these recent visits, she often doesn’t know who I am. I can tell by the searching look in her eyes, like she is trying to place me. I attempt to engage her in some kind of conversation that will help her remember, but she eventually shuts me out as if I have exhausted her. She pretends she can’t hear me. She becomes agitated. We both end up discouraged, sitting in silence. And then the TV comes on and time slips away from us until it’s time to sleep.

In 2015, my mother fell off a street curb and hit her head. It wasn’t long after this that I noticed her becoming more forgetful, more confused, more dark.

At night, when I stay over, I sleep on the couch. Her apartment, in a seniors’ facility, is small. The couch I sleep on is in the living room area between the two tiny bedrooms — Mark’s on one side and my mom’s on the other. It’s not unusual for my mom to wake up in the middle of the night when I’m there; as if she senses that someone else is sleeping nearby. Like in some weird horror movie, I’ll wake up and see my mom standing quietly nearby, watching me and puzzling over who I am. Maybe she thinks she’s dreaming. Last year, when I visited at Christmas, she seemed more uncomfortable than usual when she woke me this way.

“Hi, mom. Are you okay?” I asked her.

“Where does that go to?” she said, pointing to the door.

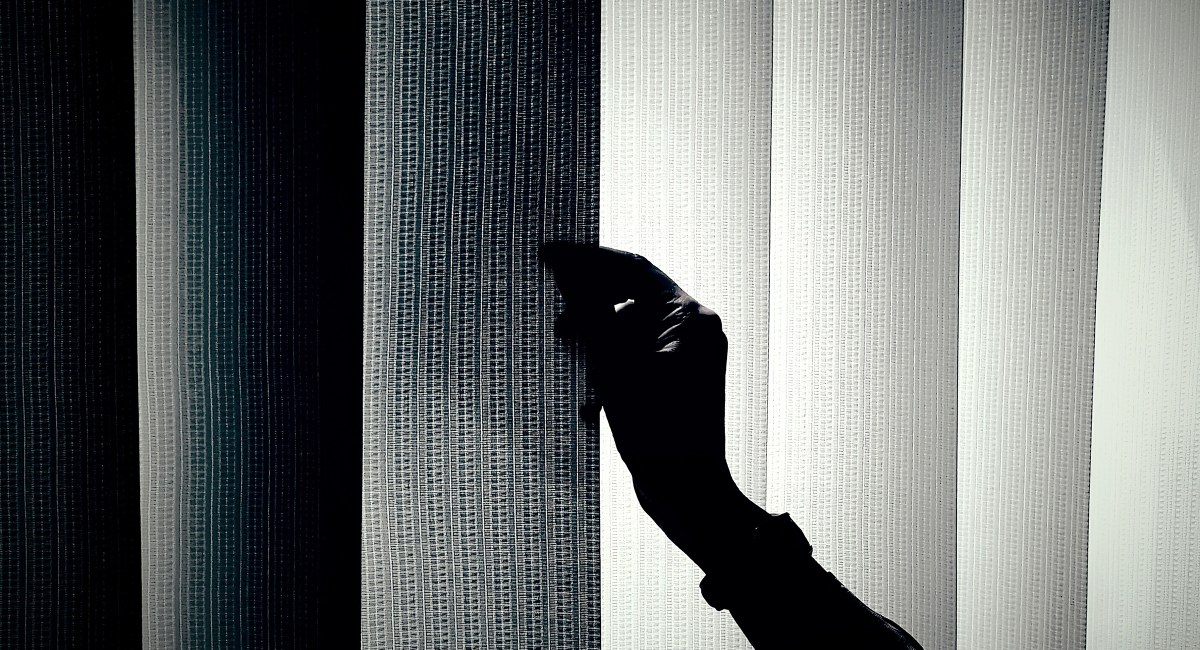

“It goes to the hallway,” I said, and thinking that she may be uncertain, I asked her if she wanted to go for a walk with me. It was freezing outside, but the hallways in her building form an easy square to walk around, as long as she doesn’t stray and go out one of the exit doors. She often walks laps out there, scuffing the brown carpet with her slow slippers. I pulled my pants on and walked around the hallway with her, hoping it would make her tired enough to eventually sleep. It was about two in the morning. When we returned to her room, she started looking out the windows, slipping her spotted, papery hands into the blinds and opening them to peer out. Her vision is so bad she probably couldn’t detect anything. “What’s out there?” she asked.

“It’s too dark and cold to go out there,” I said.

She kept looking, as if she was trying to piece something together. There were a couple of streetlights in front of her building, shining dim spotlights on a few cars parked by the sidewalk. A truck drove by, slicing through the quiet night with one headlight. “There’s someone,” she said, excitedly.

I helped her get back in bed, under her covers, but she got back up fifteen minutes later, just as I was falling asleep again. She seemed to be under the impression that we were somewhere else entirely, and that we would have to get up and move on soon, like we were drifters. She said, “I was trying to decide if I should try to sleep or what. Someone might come in and see me lying here and have a fit.” This is a common thread in her daily life — feeling like she’s not really home. She’s lived here for two years though. Before that, she lived in two other homes in Olympia — both bigger houses — for about two years each, and before that in Kennewick, Washington, where I grew up. But even Kennewick is a hazy memory to her now, though she lived there for over fifty years. When she mentions “home” she usually means her childhood home in Loma, Montana, a shrinking town where fewer than 100 people live in the middle of that giant state. She often says to me, “I’m not really sure how much longer we’ll be staying here.”

I’ve read articles about Alzheimer’s and spoken to other people who have been around it. I’m trying to understand it, to see if it can be fixed somehow. I wonder if there are tricks you can do to make people remember things, to bring them back to their current life. I read the book, The 36-Hour Day, by Nancy Mace and Peter Rabins, which is an important and helpful book on the disease. I started to record some of the conversations with my mom and then listen to them to see if I can figure out where her mind is going. At best, she is simply melancholic. Much of the time though, she’s panicked.

On recent visits, she often doesn’t know who I am. I can tell by the searching look in her eyes, like she is trying to place me.

On this late December night, I talked to her and tried to uncover what kind of thoughts she was having. I imagined her despair was like a swirl inside her head. “I don’t have anywhere to go anymore, because apparently the folks have given up the house,” she said, her mind back in a place where her parents are still alive, but in some kind of trouble. “I just hope that everything’s going to be all right. It just seems like we’ve had bad luck for months. It’s about time it’s changed,” she said, with a small sliver of hope. I told her everything was fine and she just needed some sleep. “This is your home and you can sleep here as much as you want.” I held her hand and told her I loved her.

We were not an affectionate, touching family that communicated love very often when I was growing up and this physical touch, the soft brushing of my fingers on her hands and arms, is something that still feels a bit unnatural to me. She seemed almost comforted for a moment though. “I love you too,” she said, and made a sound that came out like a laugh, but with a pained kind of sharpness to it. She wore a confused expression as she said it. Was it that she was so unused to saying those words? Was it that she’d wanted to say the words to someone, but because of her forgetfulness, was never really sure who she was saying them to? “I love everybody as far as I know and if I said I didn’t I was probably mad at you,” she said, laughing a little more, like whatever had been hurting her had stopped. It was nice to hear this — the kind of thing she’d say 10, 20, or 30 years before. A sweet nugget of warmth, with a small winking reservation. She had always showed that she loved us, but it was never an outpouring. She was slow and careful with her heart.

“One of these days, hopefully, we can forget all this and start living again,” she said, as if Alzheimer’s is something you can come back from. As far as I can tell, it’s not, but I just nodded my head. I realize I could be anyone to her — her brother, her father, her son, or maybe an old friend. Sometimes, people with Alzheimer’s can’t remember who you are but they recognize body language and will feel at ease if your demeanor is familiar and friendly. “I love you so much and I feel bad about picking on you and hoping you’ll do something for me once in a while,” she said. Maybe she thought I was Mark. I can’t imagine what he’s gone through, day after day, taking care of her. He was also the caregiver for our dad, when his health was breaking down. He died in 2008.

I told her again that I love her and that she’s not picking on anyone. I didn’t want her to feel bad, or like a burden; I think she often feels like a burden. She seemed exhausted, finally relaxing into her pillow but still talking. “Anyway, I really do appreciate what you’re trying to do for me. I just feel terrible about everything. I honestly don’t know what I’m going to do but I’m going to have to move someplace else and just start all over.” She started circling back to that same trope — this desire to “go home.” Then her voice got dark and low. “As time goes by, I might get desperate enough and shoot myself.”

The bluntness jarred me and I wasn’t sure how to respond for a few seconds. “You shouldn’t talk like that,” I said. It was late. I was tired. I was trying not to cry.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do for the rest of my life,” she continued. “But sometimes I have thought about suicide.” Her voice trailed off a little at the end, as if she was trying to think of something else, or remember where she was.

“No, you’re not going to do that,” I said. It almost felt as if she was testing me and I found myself feeling impatient. We stayed like that, her under her blankets, me sitting on the side of her bed. On her walls around us were old photos of various family members — cousins, uncles, aunts, brothers. I was in many of the photos, but with old girlfriends, an ex-wife. One photo was of my niece and her ex-husband. This array of photos was probably at least ten years out of date. I made a mental note that her photos should be updated, but then I wondered if that would be a good idea. Maybe it would be confusing.

After a silent minute, she looked at me, as if noticing me for the first time. “That man was so nice to me though,” she said. “That man that was just here. I think he went out the front door. I was trying to help him too because he kind of acted like he needed help. He was the person who told me to lie down here.”

“That was me, Mom,” I told her.

“Well, maybe so,” she answered. “I don’t really pay much attention to who’s who or who I’m talking to or what I’m saying.”

I asked her if she knew my name.

“Your name is Joe,” she said, and then started laughing like it was a joke. But she could tell I was still waiting for an answer. “Dwayne, wasn’t it?” I tried to give her a hint and told her it was a name in the family. She couldn’t remember, so I said Kevin, and she said “Oh? Okay,” as if surprised. I asked her, “Who is Kevin?” She answered, “I don’t know. I really don’t remember. That was probably a long time ago, wasn’t it?”

I’ve read articles about Alzheimer’s and spoken to other people who have been around it. I’m trying to understand it, to see if it can be fixed somehow.

I tested her with other names and asked if she knows Matt and she remembered him quicker. I asked who he is and she said, “Matt’s my son.”

Then I said the names of her other two sons. First, she had to think about Russell for a while before saying he was “not my son, but my something or other.” What about Gary, I ask her. “Gary is just Gary,” she said, and then explained further, “Gary is just a common name.”

I asked about Elinda, the daughter she gave birth to when she was seventeen and (after a youth in mental hospitals and a life of various struggles) had died just a year before. I wondered if Elinda’s absence might be a source of confusion for her, but she said quickly and correctly, “Elinda was my daughter.”

When I said my name again, she said, “I can’t place Kevin with anything.”

She tried to sit up again, turning to look out the window. She was very curious or concerned about what was outside. I told her that nobody was out there. Everyone was inside their homes, sleeping. I had my hands on her shoulders, partly to calm her, and partly to keep her in bed. I felt like I was starting to come down with a cold and desperately wanted to go back to sleep. We had been up for an hour and my phone was on her bed, recording our conversation. “I like to think of myself of not being afraid of things but I am afraid of things,” she said then. “A lot of my problem is that I don’t like people to dislike me. So I try to be overly friendly sometimes to somebody.” I told her I was the same way, and that there was nothing wrong with being overly nice.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

“I left my folks the other day,” she said. “Instead of trying to cooperate, I just got tired with them and left. Then I started feeling sorry for myself. I think I should be sent to school or something and taught how to do something.”

I can tell that her relationship with her parents is something she never felt closure with. She became pregnant in 1946, around the time she was turning 17, and even though she married the father, it was still embarrassing to her parents and they were barely in her life after that. I don’t remember them being talked about at all, even in my childhood.

While doing some internet research recently, I learned that my mom’s father died nine years before I was born, and her mother passed when I was five.

“I think they do a lot,” Mom said, speaking of them in present tense. “They expect too much sometimes, and I tried to be what they wanted me to be, but I couldn’t. When I was younger I had more insight on myself, but now I think I’d be a better person if I was married and had a husband with me all the time.” Hearing my mom voice such an old-fashioned thought made me wonder what year she was stuck in, and if that was why she married my dad.

Earlier in the day, Mom, Mark, my brother Matt, and I went out for lunch and when we returned, she became distraught. “Where did everyone go?” she said. We’ve become so used to this way of thought, we knew right away that she meant us when she said “everyone.”

In the ninety minutes between the time when we left for lunch and the time we came back, Mom had seemingly transposed our 1 o’clock bodies in her mind with entirely different people. At 2:30 in the afternoon, we were suddenly other, possibly unknown bodies to her. It almost makes you feel like you’re in a science-fiction movie. Imagine a scene where a mother is with three people in her home. Then a scene where they all get in a car and drive to lunch. Then a scene of the four of them, having lunch at a pizza restaurant buffet. Then cut to them as they return home, opening the apartment door, the mother confused, exclaiming, “Where did everyone go?” In these four scenes, the mother is played by the same actress, but there are different actors playing the other three people in each scene.

This is a common thread in her daily life — feeling like she’s not really home. When she mentions ‘home’ she usually means her childhood home in Loma, Montana.

“They should have left a note or something,” she said. She was suddenly angry, flustered. “I think it’s so rude when people do that.” She was standing in the middle of the room, her hands in front of her, palms up, like she was at a loss for words. She looked around the small apartment, as if this “everyone” were just hiding from her. It’s like the “face blindness” condition, prosopagnosia, but instead of just faces, it’s whole bodies, whole memories.

“We’re all here,” I told Mom. “There was no one else. It’s just been us today.” But she ignored my words and several more minutes of distress followed. She repeated the question, “Where did everyone go?” a few more times. Finally, Matt wrote a note on a scrap of paper and presented it to her. We’ll be back to visit soon, it said. It may seem cruel to play this kind of trick, but Mom’s mind does not work in a reasonably linear way, and we often find ourselves doing anything to make her feel safest.

I’ve tried to see if she is better in the morning, calling her on the phone as I make my breakfast in Portland. Maybe she’ll remember me. Maybe her memory is more reachable early in the day. Perhaps it’s still there when her body is rested, and it simply dwindles as the afternoons turn to night. I imagine Alzheimer’s is like a Polaroid photo in reverse — a posed family, smiling before, then fading into a milky white slab of nothing.

She usually does seem more present on the phone during the day, asking when I’ll come visit, although I’ve become unsure if she knows who I am when she’s asking me this. When I do visit though, she shuts off and doesn’t know what to do. Her Alzheimer’s makes her lose track of time and reality. She speaks of her parents in the present tense. She thinks they’re missing. She talks about how she wants to move back to Montana. She talks about it like there are people she knows there. But she doesn’t really know anyone. My mom was never social. I never remember her having friends. Surely, she must have had some. Maybe some people she worked with, when she had a job 30 or so years ago.

I think about what she’s lived through. Looking at her now, this slightly-crouched old lady with mussed-up white hair, it’s easy to forget that much of her life was a mixture of strength, forgiveness, and rebellion.

She can’t see well. She can’t hear well. The activities that brought her joy for so long — reading and quilting — are not physically possible for her anymore. All of her siblings and the family members she was closest to have passed away. I find a lot of this information about deceased relatives on a website called findagrave.com. I imagine that she feels like her life is a boring kind of hell.

I think about what she’s lived through — the teen pregnancy, three husbands, the abuses she endured from them, the daughter who was sent away for shock treatments, a boyfriend from Africa who disappeared, the family members that shunned her when she had a black baby in 1963, four years before I was born. Looking at her now, this slightly-crouched old lady with the cane and the mussed-up white hair, it’s easy to forget that much of her life was a mixture of strength, forgiveness, and rebellion.

Sometimes I wonder if this will happen to me too. Studies say that the disease is rarely passed down, but there are times when I find myself concentrating so hard on something that my memory totally freezes and stops working. I understand that’s not Alzheimer’s, but I wonder what the future holds for my memories.

Almost every day, I look out the back window in the house I live in as I wait for my coffee to heat up. I scan the backyard — the stump of the big tree that was cut down after the winter storm, the patches of grass, the tall wood fences, the birdhouse hanging high and alone off the back of the neighbor’s barn, the Japanese maple tree, the cherry trees, and the birdbath full of flickering silver water. I think back to my childhood home, in Kennewick. I would look out the window of our home and spy on my mom on Easter, as she hid Easter eggs in our yard. It was the same yard where my brothers and I would play football with the other neighborhood kids. I remember the kids’ names: Willie, Todd, Darren, Brian. I wonder if I’ll always be able to remember these things.

My mom had a life before Alzheimer’s and she was able to hold onto her memories, good and bad. I’m not sure how much longer she’ll be here on this earth, in her body, trapped in the cul-de-sac of her mental decay. It will be a moment of mercy and peace when she does breathe her last breath. These last few years of chaos for her will eventually be forgotten and we, her remaining family, will hold onto the long life of love and strength that she lived before it faded to nothing.

* * *

Kevin Sampsell is a writer, editor, and bookseller living in Portland, Oregon. His books include the novel, This Is Between Us, and the memoir, A Common Pornography.

Editor: Sari Botton

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email