Susie Cagle | Longreads | June 2015 | 21 minutes (5,160 words)

The sun was going down in East Porterville, California, diffusing gold through a thick and creamy fog, as Donna Johnson pulled into the parking lot in front of the Family Dollar.

Since the valley started running dry, this has become Johnson’s favorite store. The responsibilities were getting overwhelming for the 70-year-old: doctors visits and scans for a shoulder she injured while lifting too-heavy cases of water; a trip to the mechanic to fix the truck door busted by an overeager film crew; a stop at the bank to deposit another generous check that’s still not enough to cover the costs of everything she gives away; a million other small tasks and expenses. But at the Family Dollar she was singularly focused, in her element.

We loaded up more than we could carry—the plates, bottles of water, dish tubs and bars of soap—then turned down a two-lane road past the yellowing city golf course, past the cemetery, past the small muddy pond full of matted geese and ducks, where the water is so warm no fish can live. The sun sank a little further into the dirt.

Air grows thick in the Central Valley. It’s humid and the dust sticks together, a light film coating your skin, your clothes. Each breath a labor.

It was the rainy season, but you wouldn’t know it.

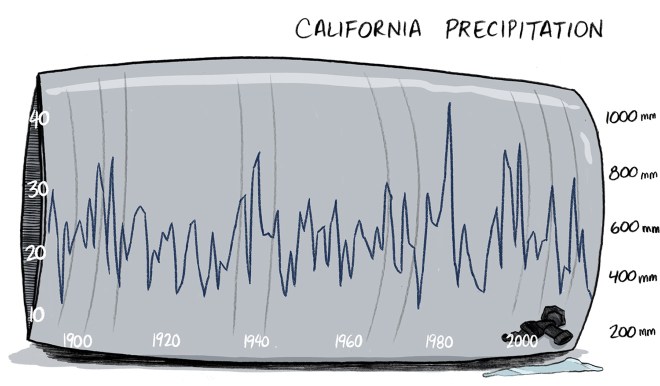

California has always been plagued. The floods and fires presented as disasters are in truth a natural lifecycle for a binge-and-purge ecosystem that was in no way formed with human life in mind. Centuries of settlers have attempted to tame this extreme landscape with increasingly ambitious feats of engineering: draining lakes until they were craters, moving rivers of water until all the fish died, drilling out the aquifers until the land sank.

This has in some ways made us very rich. California’s economy is the largest of all the U.S. states. When the plains turned to dust nearly 100 years ago, thousands migrated here, including my family, and helped to establish the Central Valley as the nation’s preeminent agricultural center. Today the region produces a full third of the produce we eat.

But now the land is purging. A spectacular drought has drawn the entire Southwest dry. Where water has long been a rival good yet inexplicably taken for granted, more than 90 percent of California is in a severe drought, with the situation in Porterville and much of the surrounding valley deemed exceptional. The state’s natural dryness has been exacerbated by a creeping global climate change and a cascade of questionable human decisions, and it has escalated with shocking speed.

Last September, Governor Jerry Brown declared the drought not just an emergency, but a disaster, releasing millions in funding for immediate aid but none for the long-term infrastructure necessary to maintain an extremely thirsty modern society.

The crisis is constant. California has always been plagued.

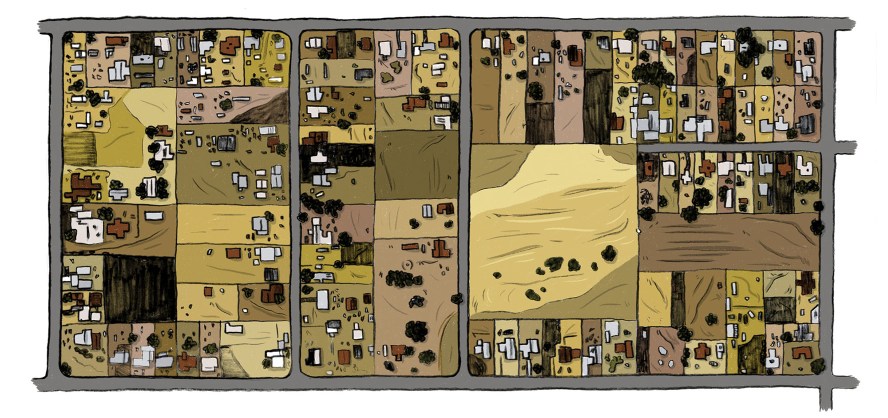

For the last year, the unincorporated and impoverished community of East Porterville has experienced some of the worst effects of this drought through a combination of exceptional factors that have coalesced to stamp out a self-sufficient subsistence that has characterized Central Valley life for many people over the last 150 years.

With no municipal water system, families rely on private wells and the groundwater those wells tap. So, too, do the farmers planting thirsty and thirstier non-native crops nearby— farmers who can drill ten times as deep as their residential neighbors for the water those plants need. Months go by without rain; the groundwater they suck up isn’t replaced. No one really knows how many of the shallow home wells have gone dry here: They thought it was 100 until they counted 500, 600, 800… that now pump only sand. In a community that prides itself on self-reliance, how do you live off the land when the land turns on you?

This is life after water. And no one knows how long it might last.

After water, there are a thousand new considerations: Is it better to cook with expensive, precious bottled water or eat fast food every night? Does this soap have animal fat in it that will stick to your skin and be harder to scrub off? Whose truck can you borrow to pick up the water you need from the fire station to bathe your babies? How dirty does it have to be for you not to drink it on a 110 degree day? How long can you live like this?

After water, what is the cost of this independence? What is the role of government and other institutions? Who bears the load of a community on the brink? How does a town stay a town?

Who brings the plates?

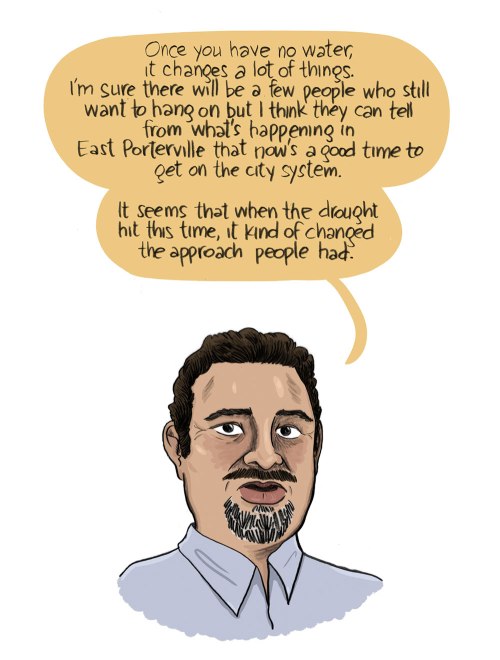

Donna Johnson grew up in Kansas before moving to Southern California, and then retiring in East Porterville, where many have come to rely on her over the last year. They call her “the Water Lady;” some even show up at her house unannounced, demanding the stuff. Johnson might be the most famous woman in East Porterville. She’s won awards from the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Ford Foundation, been profiled in newspapers and magazines around the world.

Early last year, when her well began sending up more sand than water, Johnson went door to door, asking neighbors if their wells had gone dry, too. It took weeks. She compiled a list of affected homes— a list much, much longer than the county had anticipated. She advocated for East Porterville residents at city and county meetings. She began accepting and delivering donations, filling her carport with pallets of water, emptying it, filling it again.

Porterville takes little responsibility for this unincorporated rural sprawl, which is just fine by most of the people who live in it. In theory, East Porterville should be capable of sustained self-sufficiency: It’s positioned strategically at the edge of the Tulare Basin, a few miles downhill from the Sequoia National Forest and less than a mile from the painfully named Lake Success, with the Tule river running straight through it. In theory, its underground aquifers should be easily recharged. But some wells here have been running dry four summers in a row.

Porterville, by contrast, is not just surviving, but thriving, according to its former mayor. The town of fewer than 55,000 is situated about an hour’s drive north of Bakersfield, surrounded on three sides by the dairies, ranches, and fields of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and grains that feed America and several other nations. The biggest employers are the government, the hospital, the Walmart distribution center, the casino, and Foster Farms chicken. The local median income is about two-thirds the state average. It is consistently ranked as one of the top ten most polluted cities in the country. To say that Porterville is thriving would appear to be something of an overstatement of the current condition.

A Wild West town with deeply conservative politics, Porterville is not what most think of when they think of California. Porterville supported the Confederacy in the Civil War, and made a concerted effort to secede from Tulare county in later decades. More recently, it was the only city in the state to officially endorse a ban on same sex marriage.

Today Porterville is, at least, surviving, as it has for more than 100 years. And it is changing. Since 2000, the town has grown by more than a third, in large part by annexing select swaths of its neighboring unincorporated communities, in some cases completely surrounding remaining county holdouts. The politics are shifting with the population: More than half the city is now Latino. Its wealth and education levels are on the rise. Its municipal water system, sustained by deep public wells, is still functioning without incident.

But at the edge of the basin, in the shadow of the mountains, East Porterville is drying up. And no matter how much funding the state designates for disaster relief, no matter how many water tanks the county delivers to front yards, no matter how many people Donna Johnson counts, they can’t stop it.

Before Porterville, before the almonds and the gold, before people, this was all an ancient sea. For the better part of a million years, the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys that together make up the middle of California were home to a variety of prehistoric ocean life. When it all dried up, the basin was left lush, swampy, and remarkably fertile above an abundance of underground aquifers.

The loose-knit Yokut Indian tribes of the Central Valley lived here for hundreds of years, in communities scattered along the Tule river. The Spanish clung to California’s coasts, disinterested in the inland areas, where nearly 20,000 Yokut were undisturbed until James Marshall found a bit of shiny metal at a lumber mill more than 100 miles north. The ensuing Gold Rush drove tens of thousands of new residents to California, some of whom stopped on their way to the mines to instead settle Porterville and begin cultivating crops. In 1856, the new settlers waged war on the Yokut—by 1910, only about 600 were left. But new Porterville thrived: The railroad came, then the businesses and banks from San Francisco, then the mineral mines.

More migration begat more agriculture—tens of thousands of new Golden State settlers required a new local food system to sustain them and their new cities. The people needed crops, and the crops needed water, a resource those early pioneer farmers had taken for granted when they planted hundreds of square miles of thirsty fields under all that California sunshine. It took 60 years of droughts, floods, and federal wrangling before the Bureau of Reclamation devised a complex system of pump plants, canals, and aqueducts that would funnel stored water from the soggy Sacramento-San Joaquin river delta down into the farms and communities of the Central Valley. The massive, sprawling Central Valley Water Project took nearly 40 more years to build.

While California was reengineering its geology to better serve its new society, another part of the country was grappling with its own water woes—and coming up dry. The Homestead Act and transnational railroad had encouraged development and agriculture across the West. In the Great Plains, a few good wet years led new settlers to believe they could farm the land without worry. They ploughed deep, destroyed native grasses, and set the stage for sweeping environmental devastation.

In the early 1930s, a period of drought set upon the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles. The land had not just dried up, but evolved into a swirling, destructive, and near-constant storm of dirt. The ensuing Dust Bowl sent more people escaping West than the Gold Rush had enticed with the promise of wealth.

Driven from her Texas farm as a child, my grandmother Bernadene Garrett arrived in Porterville with her parents, two sisters, and a brother who would die in the next war. The family established and cultivated a modest tomato farm. But in dry years, the dust still swirled.

At 14, Bernadene caught valley fever, caused by a fungus that lives in loamy soil across the southwest, coming alive and airborne in the dry heat of late summer. The spores root down into your lungs and can never truly be displaced. She dropped out of high school for two years, and suffered symptoms of the disease for the rest of her life.

In recent years, the fever has been making a comeback, flying up from the loose Valley dust, infecting thousands every year. There is still no cure and no preventative vaccine.

Whether it was the farm, the fever, or the unyielding conservative and religious politics of the place, I can’t know, but Bernadene wanted out. At 19, she eloped with my grandfather—at the time, a lawyer; later, a drunk—and didn’t look back.

Donna Johnson pulled into a long dirt driveway, and began unloading what she brought: the plates, the water, the plastic dish tubs and the bars of soap. The supplies were purchased with small donations or Johnson’s own funds. Door-to-door assistance has been the nature of the Water Lady’s operations for much of the last year. Sometimes there are other volunteers, assistants, but they usually last only a day or two. It’s just too hard.

Lately it’s gotten a little easier. The county started making monthly water deliveries, cases of Sparkletts for cooking and drinking. But the logistics are haphazard and confused: With multiple trailers and homes on one property, some people are often skipped.

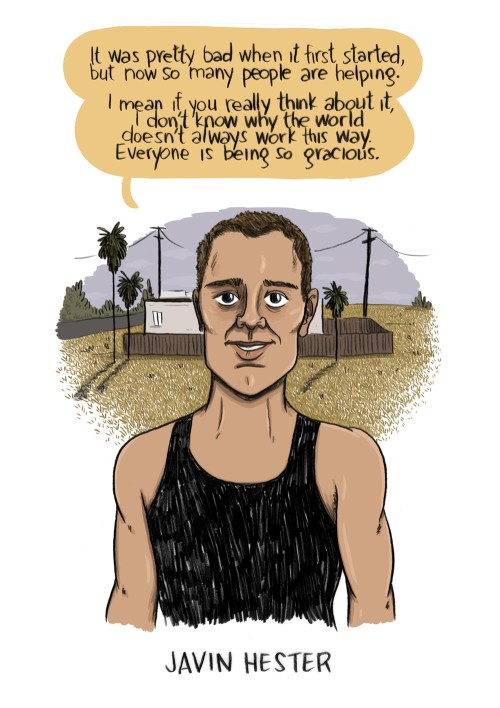

Javin Hester, 23, emerged from his trailer with good news: They strung a long hose from a neighboring church’s deep well, and now had enough water shared amongst the four homes here for one person to take a shower at a time. Sometimes the water is the color of rust, or urine, but sometimes it’s not—it’s water, and it’s theirs.

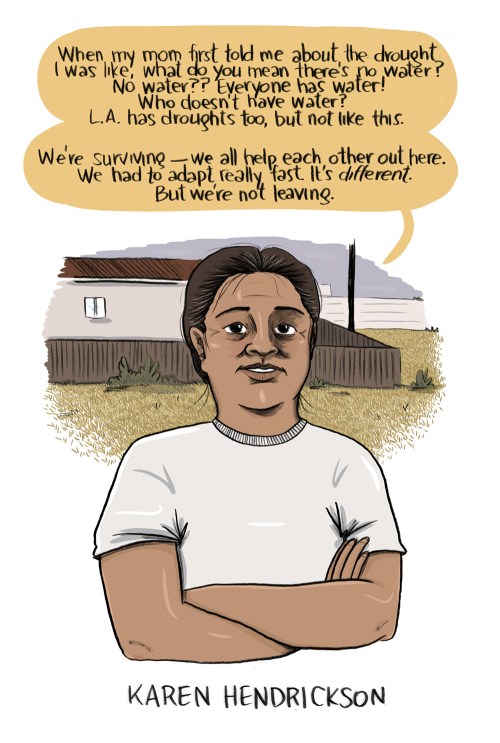

The storms this season brought far more wind than rain, and the landscape is littered with crisp, fallen dead trees, trees that had survived for generations, through many lesser droughts. A tall pine snapped and took out the power here for two days recently; its remnants were chopped and piled near Karen Hendrickson’s front door.

Hendrickson, 48, moved here with her daughter from Los Angeles at the height of the dry summer, to take care of her ailing mother. It was a lot to get used to, even before the water ran out. When her mother died in November, she left Karen the house.

Of Tulare County’s nearly half million residents, about 15 percent are living outside of municipal boundaries and large water infrastructure. This is not East Porterville’s burden to bear alone: Residential wells are going dry across the San Joaquin Valley. And in the spirit of the state’s wild, individualist founding, California provides no regulations or protections for private wells on private lands.

When Johnson delivered her list of dry homes to the county, there was no agency or aid program in place to organize and fund emergency infrastructure and supplies. This simply hadn’t happened before. There are assistance programs, grants, and low-interest loans available to drill new wells for low-income and elderly residents through state disaster funds and the Department of Agriculture. Otherwise, a new well could run upwards of $20,000.

This is the libertarian trade-off of rural residential life: Less government means less help, but also less restriction. There are no building codes to follow, and no rules about raising as many chickens, goats, and horses as you’d like.

Most in East Porterville have stayed, at least for now. But a place once defined by its self-sufficiency has become increasingly codependent. Were it not for government, nonprofits, and community assistance, this would all be dust.

Javin Hester’s grandfather Bill Wiggins inherited their property from a friend, and despite his advanced age, manages it to the best of his abilities—no one here has any complaints.

Talking about her landlord, Hendrickson’s voice cracked. She teared up. “He’s helped us so much. He’s done so much more than he should.”

But for every Bill Wiggins, there is a horror story about another house just a block over there, where the landlord threatened to evict the family if they asked for county assistance. For every Donna Johnson, there is someone hoarding all the Sparkletts gallons that were delivered for their entire apartment building, or refusing to help the young mother who knocks on their door, desperate for water, instead turning her in to Child Protective Services.

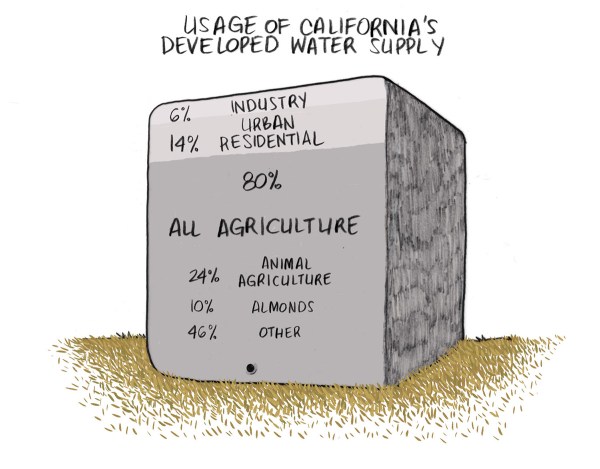

There is nothing on which we rely so completely for survival, and yet we have done precious little to prevent its waste, its sale, and its destruction. America’s water footprint is the biggest in the world, per capita. Where nearly 800 million people lack access to clean water around the globe, the U.S. uses it to green millions of acres of golf courses, flood millions of acres of non-native crops, and grow millions of acres of feed for millions of the cows we rely on for food.

California’s trouble with water is not strictly an issue of supply, but also one of priorities. Though little blood has been spilled, the nation’s water wars have arguably been some of the fiercest and most pivotal in shaping our modern communities, and in no place has that clash been as hot as in California. The state’s hierarchy of licensed water rights is perhaps the most convoluted in the world, a strictly regulated system of “finders keepers” that leaves already strained water resources exceptionally overbooked.

The drought has had a cascading effect across this complex supply chain. Much of California’s fresh water is naturally stored in the Sierra snowpack, which is now at its lowest level ever recorded. The loss of natural resources places more pressure on the engineering meant to shuttle water around the state—not to where it is most needed or best used, but where it has been most assuredly promised.

In early 2014, the Bureau of Reclamation reallocated that year’s limited supply of Central Valley Project water, sending precisely none to the San Joaquin Valley farms that are contracted for up to nearly 2 million acre-feet. In 2015, the Bureau issued the same allocation, calling the situation “dire.”

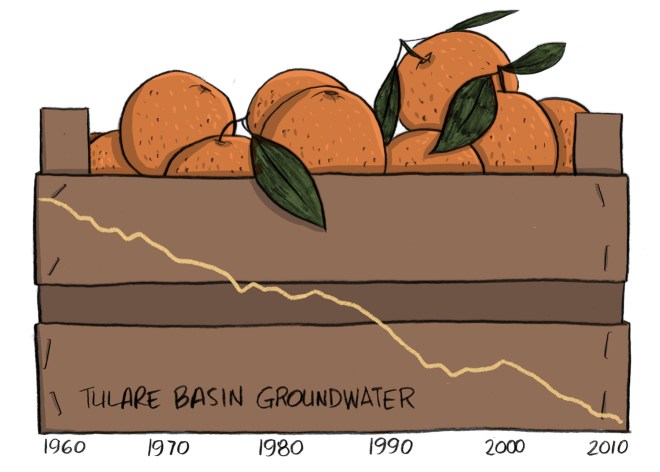

Receiving nothing from nature and nothing from the government, farmers dug deep. Some tore out especially thirsty non-native crops, leaving fields fallow. Others dug deeper, drilling hundreds of feet down into the valley’s precious, ancient aquifers, pumping them out far faster than nature can replace them. If they pump more than they need, that water can be sold back to water districts, which then turn around and sell it to other thirsty farmers. Since 2011, the number of well permits has more than doubled in Tulare County, which issues more than any other county in the Central Valley.

Here private land rights have always come with groundwater rights: Whoever has the resources to drill the deepest wins. California was the last state in the U.S. without laws regulating its groundwater resources until 2014, when Governor Jerry Brown signed into law the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, tasking local governments with tracking water use and enforcing limits. Even so, it is still the last state without regulations—California won’t release standards for what “groundwater management” means until 2016, and counties won’t begin implementing them until 2017.

So far, these are the only restrictions placed on the state’s agriculture business. When Governor Jerry Brown stood in the dry Sierra mountains to announce California’s first-ever mandatory water cutback, he targeted lawns, not crops. Farmers will be required to track and report more information about their water use to the state, but their fields won’t have to do without, though some irrigators have offered to cut back.

Tulare county has three sub basins—three underground pools that farmers are draining, quickly, to irrigate a wide variety of crops increasingly responsive not just to local and national tastes, but to international ones as well.

This is a multibillion-dollar industry, but it is not necessarily good business. For all that water, agriculture produces just about 2 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. But that 2 percent, while small, is vital: It shaped the state’s physicality and identity from its earliest pioneer origins and today feeds Americans from coast to coast. Its political lobby is immensely powerful, with deep ties across party lines.

The state constitution protects against “the waste or unreasonable use or unreasonable method of use of water.” This could be a tremendous tool for the state government to use in prioritizing residents over business, were it interested in doing so.

California’s agriculture business might be, at this point, too big to fail.

But this was not the water war anyone expected.

Central Valley activists have worked for years to rein in the environmental degradation wrought by massive agribusiness. Farmers pile fertilizers on their fields, tainting the groundwater with high levels of nitrates, concentrated over miles and miles of farmland. Rural residents living with well water are exposed to significant health risks: excessive nitrate consumption reduces the body’s ability to send oxygen to vital tissues, which is especially dangerous to babies.

These are all problems not of nature, but of corporate scale. When they drill down 500, 800, 1,000 feet to drain the sub-basin and load nitrate-heavy fertilizers on their fields, individual farms are acting in their own best corporate interest. Some of those irrigation wells have run dry, too. The small rural residential communities nestled in between those farms, the ones that once seemed so sustainable with their own water supplies and arable land, have been sacrificed to a parched supply chain that privileges water-logged coastal cities and a global food system.

But it’s a supply chain on which these communities also rely, as nearly 36 percent of East Porterville’s labor force works in local agriculture.

When the wells began to pump dry, the county tested the little water that remained, and found that just like so many other towns scattered across the valley, it too was contaminated with nitrates. This made residents eligible for aid under the state’s Cleanup and Abatement fund. It also put East Porterville’s future in a new kind of jeopardy: No amount of rain can fix this.

The last winter brought a strained optimism to East Porterville, but it brought little rain. The water that did fall—less than 2.5 inches—beaded off the slick, arid ground, flooding some low-lying neighborhoods before evaporating in the hot sun.

Where California thought it was engineering the land to meet society’s demands, it didn’t account much for nature’s. The state’s Mediterranean and semidesert ecosystems are prone to cyclical drought cycles, feast or famine, but creeping global climate change threatens to further exaggerate those already extreme conditions. East Porterville can pray for rain all year, but the period between 2011 and 2014 was the state’s hottest and driest on record.

If East Porterville’s plight highlights the ability of a community to unite in a disaster, it also exposes the difficulty of official infrastructure to do the same. Water trickles here now, not through wells or pipes but an ad-hoc system of community, nonprofit, local, regional, state, and federal government aid.

Nonprofits have delivered large water tanks to some families, and the county is working on a program to provide larger ones. The state Emergency Management Agency is drilling a new deep well for Porterville, so the city will have the capacity to set aside up to 2 million gallons of water for the East each month—enough for about one fifth of the town. But that water won’t be pumped for several months, and the city refuses to fill the county’s tanks in the meantime.

Every arrangement is strained; every solution, temporary. The situation is as fluid as the water no one has.

Last fall, the county and city set up a temporary free shower service at an East Porterville church where Rev. Roman Hernandez has been accepting and dispensing donations of water and bread rolling in from as far away as Missouri. Their own well went out more than six months ago.

It was already dark by the time we arrived at the house Angelica Galleos shares with her husband and two young daughters, the sky a chalky indigo. Their water tank sat squarely in the small front yard, just beyond the living room window. On this day it was empty.

Galleos and her family moved to East Porterville from Mexico in 2007. When their well stopped pumping, more than a year ago, she considered going back. Instead she worked with Donna Johnson, translating for the majority of local residents who speak only Spanish. On their first day together, they saw an old man living in conditions so dire, they didn’t know how to help. After sobbing together in the car, Galleos decided to stay.

Everyone agrees: Things are better than they have been. But the crisis of concerted drought isn’t the first day without water, but the persistent and plodding reality of it. This is the nightmare scenario that motivates doomsday preppers to load up secure underground bunkers with water tanks. A true crisis is so much more mundane for people like Angelica Galleos. It’s cold sponge baths when the public showers are too crowded in the morning; four hours at the only crowded laundromat, jockeying for the few big machines; every meal served on paper plates. It’s a kind of shame. It’s your child with the lice that you just can’t get rid of; the outhouse your husband built in the backyard that you don’t want anyone to see. It’s not a moment but a constant, wearing you down one day at a time like a small stone at the bottom of a river.

The city water line runs right down Galleos’s street, past her house and her empty water tank. When I asked if she might want to hook into the municipal water system, she and Johnson looked at each other and giggled.

Rural life in America is dying, and not slowly. In an ever more connected age, society is moving closer together. Today only 19 percent of the country’s population lives outside cities and suburbs. It’s the last vestige of an older, more libertarian time, when to live in the West meant to be autonomous, wild, and often uncomfortable. People did not move to California for its established social structures, but for what they could pull out of the ground with their own hands.

For the Central Valley’s Latino immigrant communities, rural freedom cuts both ways. While they are disconnected from municipal convenience, they’re also sheltered from government scrutiny, a condition more vital than running water for those who are undocumented.

Just like the farmers who pump out the precious aquifers, people in East Porterville want to be able to do what they please with their land. But unlike those farmers, East Porterville is small, and it is poor, and it is in no one’s best interest to save its old way of life. It does not have a powerful political lobby, or substantial private resources. Some of the renters have already started to pack up, and others are reconsidering city annexation.

Ideology is not the only thing keeping East Porterville plagued. Even when they want to join the city, it is not always so easy. Laying new infrastructure is expensive for both Porterville and property owners, and there are sometimes insurmountable political hurdles.

The city water line that feeds the showers at Rev. Roman Hernandez’s church runs right up to the edge of his property, not 100 feet from the front door.

And so East Porterville can no longer survive by grit alone. Over the next three decades, Porterville plans to slowly annex the East, bit by bit. Those who want to cling to rural life have dismally limited options: They will have to draw upon their own personal wealth and dig deeper, or embrace a different kind of community governance. Some Central Valley communities plagued by private well failure have teamed up to form community water boards and dig shared, community wells with the help of organizing nonprofits—a system that would still require public elections and private water bills.

If there were any time for the myth of California to crumble, now seems to be it. The West is still bound up and driven by an idea of itself as a place where the pioneer spirit won out, Manifest Destiny achieved, nature dominated, tamed. California has a deeply uncomfortable relationship with its own history. It is a place in a constant state of reinvention, a land of bright blazing future, tenuous present, and little to no past.

In downtown Porterville, an antique store boasts the best collection of local history, xeroxed chapbooks filled with brief anecdotes of prominent local families and industry. The city museum is a collection of donated trinkets: dozens of samples of different barbed wires; hand-woven baskets from Native American tribes that lived hundreds of miles away; a porcelain doll collection; newspaper clippings from World War II; old musical instruments. You could spend all day there and learn nearly nothing.

We were grossly irresponsible stewards of this land. It did not go dry at nature’s behest alone. We would do well not to forget.

I came to Porterville looking for my own history, too. This was where my family first found California, as dust-covered refugees of a terrible drought. But they didn’t choose this rural life of pioneer spirit and self-sufficiency. My family left Porterville long before the water began to run out, settling in milder parts of California, coastal towns that don’t worry for their share of antiquated water rights. They reinvented themselves, and never spoke of what came before.

After water, I have so many more questions: Did you think the water would last forever? Can you believe it’s happening again, and here? What would you have done? But everyone I could’ve asked is gone now. The addresses on their Census surveys are now empty fields, and whatever there once was of Garrett Tomatoes has been lost, too, to time.

On my last day in Porterville, I visited the graveyard where my great-grandmother is buried, the mother of my father’s father, a man I never met, who has excised any trace of himself and his life here from every online ancestry database. I looked for my name chipped away in a piece of stone. I was so conspicuous in this search that the groundskeepers seemed worried for me, asked if I needed help. They looked up Essie Cagle, and directed me a few aisles away, to an unmarked plot covered in a dry carpet of short yellow grass that was crispy to the touch.

We disregard the past at our own peril. We forget the great regional destruction of the Dust Bowl, a destruction that came about not simply at nature’s behest but in no small part by way of shortsighted farming practices. We forget Owens Lake, drained dry to feed a young and hungry Los Angeles, now the country’s greatest source of dust pollution. We forget what this place was like before we got here, and we forget the hundreds and thousands of miles of infrastructure we built to carry the water we needed to make it California, this California, the one with which we have been so passionate and so careless.

If there were any time for the myth of California to crumble, now must be it.

We could double down on the self-righteousness that delivered us here by reviving old plans to import water from Northern California, from Alaska, from Canada, despite the potential for further environmental harm. We could attempt other grand feats of engineering, desalination plants, water pipelines. We could rip out all those crops, two valleys worth of crops, billions of dollars worth of crops, and start over in another part of the country. We could pray for rain, or to be delivered from our own folly. Or we could reconsider our priorities.

But we certainly can’t dig any deeper.

* * *

Susie Cagle is a journalist and illustrator based in Oakland, California.

* * *

Editor: Mark Armstrong; Fact-checker: Brendan O’Connor

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email