This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

Lauren Stroh | Longreads | March 2022 | 23 minutes (6,171 words)

Once upon a time, James Doxey lived with his wife in an inherited home that had served their family for generations. When Hurricane Audrey flooded homes from their foundations in 1957, survivors swam to its porch. The storm surge had moved 20 miles inland overnight, catching them in their sleep. More than 500 people died. Their home survived every subsequent storm that hit Southwest Louisiana until Hurricane Laura came through in summer 2020. What remains is a stout set of concrete stairs. They lead to a slab. Once upon a time, they framed his front door.

Down the road I meet Angela, her sister-in-law Victoria, and her father, Carl James, in the camper trailer they bought after losing their first home. When hurricanes come, they drive it off the lot.

These are some of the people still left in Cameron Parish. There is nowhere else they would ever go.

Cameron Parish is Louisiana’s largest by landmass, once made up of thousands of miles of grass, marshland, and water. So much of this wilderness has already washed into the Gulf. Louisiana’s coast is among the most rapidly disappearing places on earth: What is lost amounts roughly to the size of the state of Delaware; what is left continues to go.

Louisiana’s coast is among the most rapidly disappearing places on earth: What is lost amounts roughly to the size of the state of Delaware; what is left continues to go.

Carl James Trahan: I know since 1969, I own some property out here on Hackberry Beach. From 1969, we have lost 1,800 feet of land.

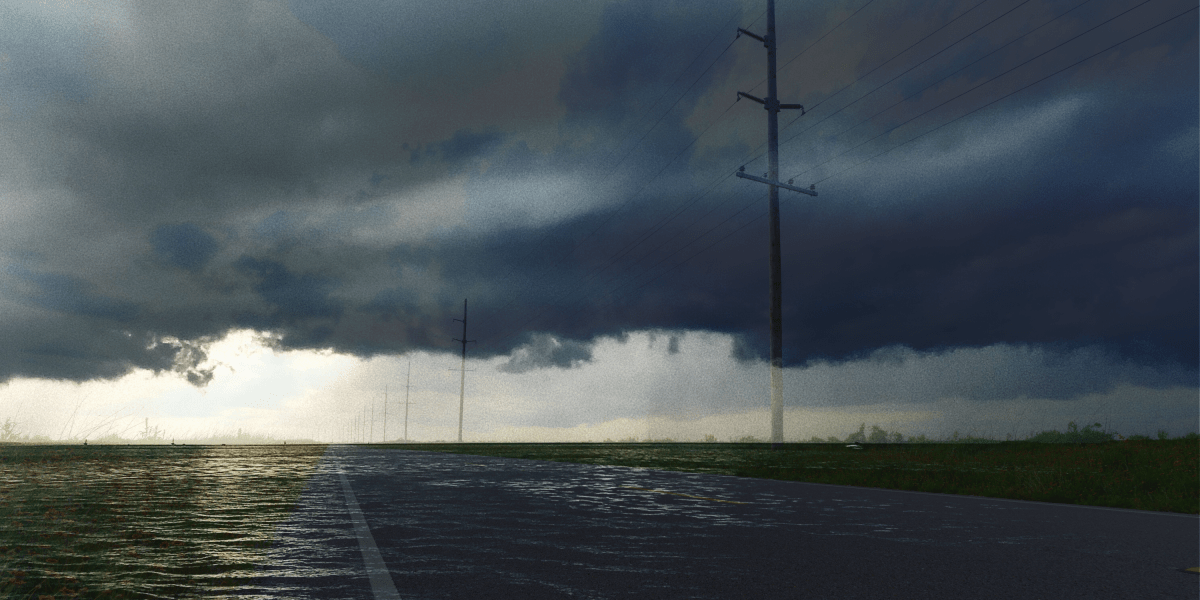

If you’ve never been out there, let me draw you a map. You go south from Lake Charles, the closest city inland, over Conway LeBleu, the most beautiful bridge in the world, this tall elegant winnowy thing, where you look out over all of the marsh covering the last stretch of Louisiana’s Gulf Coast. You ride down a two-lane highway with water rising up on either side of the car. You’re almost scared to go out there, scared you’ll run right off the side of the road. I hit a snake crossing in front of me, saw pink herons spring up above my windshield, pumped gas in floodwater up to my calves when it came in during high tide. I got lost, had to turn around, and feared for my life. Folks out there drive trucks for good reason — when the tide comes in, it floods over the main road.

Despite its size, Cameron is now one of Louisiana’s most sparsely inhabited parishes, due to its proximity to our eroding coast and vulnerability to hurricanes. The population splintered after Audrey (1957), then Rita (2005), then Ike (2008), and then Laura (2020) and Delta (2020). Before Rita, several thousand people lived out there; after Laura and Delta:

Angela Trahan Doxey: A lot of people left.

For good?

Carl James Trahan: Yeah there’s probably less than 50% come back.

How many people live here right now?

Carl James Trahan: Here? On this ridge?

Yeah that’s what I mean, the people that are from here, live here.

Carl James Trahan: They ain’t many. They ain’t many. They ain’t many left.

Hurricane Laura (August 2020) was the strongest to hit the state in over 150 years. She reversed a river in Texas for 12 straight hours, damaged nearly 900,000 properties, killed between 300 and 400 head of cattle, flooded 80-100 thousand acres of rice fields, and destroyed the entire transmission system in and around Lake Charles. Grid reconstruction took over a month, though they are still running substations off of generators out in Cameron Parish.

When Hurricane Delta (October 2020) followed a little over a month later, there was no fixing them up. It was May 2021 when I went and the houses left were totally done for, as if they had been mauled and left for dead. I passed contents strewn in both directions for miles driving in. Tarps hung tattered from their roofs, blue flags of surrender. The front walls were torn off so you could see straight through to the back. They sat tall on stilts up to 17 feet high to meet the insurance code, ruined haunted houses on this greenest bit of earth.

Carl James Trahan: This is the third time I’ve started over in my life.

Angela Trahan Doxey: I did it as a kid, as a parent.

Carl James Trahan: Rita, Ike, and Laura — the third time I’ve lost everything. It’s expensive. [laughs]

After a certain point you stop buying stuff.

Carl James Trahan: Well, that’s why we ended up in campers now.

Angela Trahan Doxey: It’s more permanent. You get attached to less. You start buying less after the first hurricane or second hurricane — you learn what you need that’s more important to pack up and what matters more.

Why did I go? I grew up in Lake Charles, not far, about the closest city inland from the coast. It is a small town, sweet and southern and kind of like Mayberry, where everybody knows everybody and spends their whole life driving up and down the same two roads. It was a charming, if not a superficially unremarkable place, to grow up in, like many other close-knit communities littered across the South. We have coffee at the diner. We have dinner in front of the television most weeknights.

Get the Longreads Top 5 Email

Kickstart your weekend by getting the week’s best reads, hand-picked and introduced by Longreads editors, delivered to your inbox every Friday morning.

But everything has changed: It is America’s most weather-battered city after the litany of natural disasters that struck it in the past year-and-a-half — two hurricanes, an ice storm, a thousand-year flood, and then tornadoes. In 2020, the New York Times identified it as the city with the highest number of displaced residents in America. You drive up and down those streets and it’s as if time has stopped — despite whatever progress that recovery efforts have made, it still looks bombed. In May 2021, my mom lost about everything inside the house I grew up in during that flood; we walked furniture, photographs, and 15 years of moldy ballet costumes out to the side of the road. From our kitchen window, I watched people take what they could salvage from our trash: wooden furniture that sat in sewage for five hours until the water receded, old clothes that stank of mildew and fetid rot.

Why did I go? I know that when storms hit us, they hit Cameron first. I know we spent over a year after Hurricanes Laura and Delta without federal aid, waiting in hope and agony with bated breath. I know that when that aid did arrive, it failed us: $600 million dollars to address $3 billion in unmet housing needs, damaged schools and businesses, debris removal, and infrastructure. I know that $2.7 billion was allocated toward Hurricane Ida recovery in New Orleans down the road only after a month or so. I assume that what little we get in Lake Charles, those out in Cameron get even less. So when you consider the devastation we were subjected to and how it compounded after more than a year of no aid, just federal neglect — they got next to nothing at all.

I wanted to understand what failures of government, mutual aid, and human decency led us here — well over a year later with a region still totally undone. I wanted to understand the reasons the people in charge failed us, how they could live with themselves in spite of it, and why so few people outside the region heard what happened here or gave a shit if they did.

It is true it is a news desert; the closest rag inland is the American Press in Lake Charles, which functions as a community bulletin board. Facebook is how people communicate with each other. But this community is small, insular, and not particularly well-off — our friend lists mostly read of one another. If you weren’t around last year (it is not some destination), it is unlikely you’d ever know what was going on.

But people in positions of power and influence did visit: Donald Trump took photos in front of my friend Jack’s house while he was still president and passed out autographed portraits of himself, which he invited city officials to sell on eBay to help with the cost of recovery and repairs. Joe Biden didn’t do much better: He promised aid, then raised flood insurance premiums for at least five million homeowners in predominantly working class coastal communities instead. I get it: It’s not a politically advantageous cause. But this is not a partisan issue. It is a crisis of conscience. It is a constitutional obligation — and even then, so many are excluded from aid arbitrarily (the indigenous, immigrants, those incarcerated, those without homes). These are Americans who have been left to fend for themselves on the forefront of climate change. They lost the better part of everything they worked their whole lives to own. They pay their taxes. They fought in all of America’s stupid wars.

These are Americans who have been left to fend for themselves on the forefront of climate change. They lost the better part of everything they worked their whole lives to own. They pay their taxes. They fought in all of America’s stupid wars.

If you don’t quite see it yet, I will tell you. Out in Cameron it is just between you and God. There is no other witness. It is just you and the water and the earth and something mystic up in the sky watching over. The rare neighbor is 20 or so miles down the road. Mr. Doxey and I get around to talking about what happens if you’re unlucky enough to have a heart attack — there is no hospital. He laughs at me, no hesitation: “You die!”

The dead and the living

Just how bad did it get, I imagine you wonder. It was hell. It still is. There are at least 100 caskets with corpses rotting inside them in trailers out in Cameron Parish and probably 20 body bags. They came up after Hurricane Laura, when the 17-foot storm surge in Creole flooded them away. Reburials are delayed while the state has yet to distribute money necessary to fix the cemeteries and reinter them in new graves.

I talked to Patrick Hebert, a marsh contractor who specializes in levee and terrace construction, debris clearing, excavation, dozer work, and oil spill cleanup. He handled the retrieval himself, along with his small crew, hunting down remains in Cameron’s bogs and marsh.

Patrick Hebert: Right after the storm we started picking them up and bringing them to my shop.

And that’s in Sweet Lake, right?

Patrick Hebert: Yes. And then we just stored ’em and I didn’t know what else to do, ya know?

Right, what a hard job.

Patrick Hebert: Yeah it’s not for the faint of heart, I’ll tell you that.

Are they all in caskets or are you finding … ?

Patrick Hebert: So, like, 90% of the time it’s kind of a boring deal, you can pull right up with an air boat and two guys can usually get the casket on the boat. It’s very uneventful. But about 10% of the time you’re gonna have some issue like maybe the casket is underwater or full of water and mud and then we can’t physically … like, the casket will just break apart if you try to pick it up. And it’s too heavy for men to pick up. So then we have to cut ’em open and put the body in a body bag or whatever we can find in there. I had about 75 caskets stacked up in the back of my shop, just covered up for tarps for quite a while.

Do you have any idea how long they were left there?

Patrick Hebert: You know, it was probably 60 or 90 days before we saw somebody from the Attorney General’s office actually come to my shop.

And so at that point they went and moved them to Creole, correct?

Patrick Hebert: Right. We loaded them in some 18-wheeler van trailers and they pulled … well, I actually pulled ’em. I brought ’em all to Creole and they just sat there and nothin’s happened since, ya know? They’re renting the trailers to leave the bodies in but they haven’t moved forward with doing anything yet. You know? At least have them more identified because they still have the identification tags on the caskets and we recorded it as we picked them up. And I know at least half of ’em.

Right, that’s how Cameron is, everybody is family more or less.

Patrick Hebert: Oh yeah, yeah. That’s kinda why we did it with Rita, because, shit, half of ’em that I was picking up I knew who they were or I at least knew their kids. Ya know? I’m a wetland general contractor. We really do all of our work in the marsh. I got marsh buggies and air boats. So we’re out there all the time. I mean, you’re on a job and you run across a casket sittin’ somewhere you can’t not pick it up. You know?

Of course not.

Patrick Hebert: I mean, shit.

You must feel traumatized at times.

Patrick Hebert: I mean, I’m gonna be honest with ya, I’m just not that kinda guy. It doesn’t bother me as much as it bothers other people apparently, ya know? The first time I went and did that in ’05, it’s kind of a funny story, but one of my airboat drivers grew up in the funeral home business and he was actually a licensed mortician, okay? So he was good with all that. It didn’t bother him one bit. And he and I were the first ones to start pickin’ ’em up. And he was so nonchalant about it that it kind of rubbed off on me like well, you know, I guess it’s not that big a deal; it’s just a body and we’ll get it done. I don’t have nightmares about it or anything like that… although I’m sure lots of people would if they saw some of the stuff I saw.

Do you mind telling me what you’ve seen?

Patrick Hebert: Well, like I said, 90% of the time we don’t even open the casket. But about 10% of the time there’s gonna be some issue: They’re gonna be full of water, or perhaps it’s a family that’s been callin’ about one and I’ve got a description on a casket so we’ll open the casket to make sure what clothes they had on so we could help identify ’em.

I ask a mortician what dead bodies look like. She tells me after a certain point they turn pitch black; it takes a while to get down to just bones.

I call Ryan Seidmann, who runs the state’s Cemetery Response Task Force through the Attorney General’s Office, to confirm that what Patrick said was true.

I’m curious about the situation with the caskets that are being held in Cameron Parish in the trailers. Why are they being held in these trailers instead of reburied?

Ryan Seidmann: Because … well, there are roughly two answers to that. Number one, not all of them are able to be identified based upon what is on the exterior of the caskets. So only about half of them are known individuals. And then, for those, we are still waiting in many cases on FEMA funding to repair the graves that they came out of before they can go back. So those are just kind of in a holding pattern for their graves to be repaired, which are in turn in a holding pattern from FEMA for the funding.

The ineptitude continues. Danny Lavergne, the director of Cameron’s Office of Emergency Preparedness, tells me it took 51 weeks for FEMA to get 201 people housed in mobile housing units after Hurricane Laura. For months they refused to place camper trailers in a flood zone before abruptly reversing that decision without reason or explanation. That’s how arbitrary bureaucracy can be. But it fucks up your life: For nine months, 201 people were homeless and waiting. They made do in loved ones’ living rooms, in their cars, in hotel rooms they had to drive in from situated far and wide across the state. People lived this way through the fall and into spring — throughout the pandemic in 2020, when at times Louisiana suffered among the highest caseloads in the United States, long before there were any vaccines. Cameron’s only hospital is still operating out of a tent with limited services. Lake Charles has no homeless shelter, and all the hotels and apartments in close vicinity were damaged or price gouged to match the demand for livable housing. In the meantime, while they waited on FEMA to coordinate temporary housing, do tell me — where exactly were these people supposed to go?

I asked Angela and Carl what they got in FEMA assistance — only $500 for immediate recovery expenses. They were denied for housing assistance, lodging reimbursement, and the cost of their generator. Meanwhile, I know people in New Orleans that had no damage from Hurricane Ida and got $1,500 fast, while most everyone in Cameron lost everything that they owned. There is no equity in the economics FEMA uses to justify their system of aid. In Cameron Parish, folks make their living selling bait for fish in what must be one of the most polluted bodies of water on earth — y’all saw that video of the Gulf of Mexico on fire after a gas leak a few months ago. It is also significantly more difficult to access material goods in rural places when resources are scarce after disasters and everything costs more to import in the first place. If you choose not to buy something that costs a lot at the one store that has goods in stock, where else are you gonna go?

I remember after Rita, my mom told me they gave her $1,500 after the storm.

Angela Trahan Doxey: Sure.

And then after this storm she applied and they only gave her $500. I’m wondering if people around here got any money after the storm. [Laughter] No?

Victoria Trahan: All we got was the $500 and we got denied for everything else.

Carl tells me he believes Hurricane Laura’s wind speeds were a lot higher than the 153 mph logged in official reports. He claims that on the crane out in Cameron they registered 202 mph and 198 mph at the Port of Lake Charles. I looked into it but couldn’t find the numbers he mentioned. But I did speak with Roger Erickson, a meteorologist working with the National Weather Service in Lake Charles, who led me to believe what Carl said just might be true:

Do you know at what point the weather instruments that were measuring everything went offline?

Roger Erickson: I wanna say the radar and the observations both went out about the same time. It was around one o’clock in the morning.

So it was before the storm hit.

Roger Erickson: Right. Well, I mean, the eye was still moving on shore, but the eye wasn’t up over us yet for another hour.

Do you have any idea what the strongest wind was?

Roger Erickson: Yeah. Well in terms of actual numbers that we got, there’s 133, 134, 135 numbers.

Why do you use (air) quotations when you say that?

Roger Erickson: Because it was higher than that. But that’s the —

How much higher?

Roger Erickson: In my opinion it’s probably gonna be in the 140 to 150 range from the gusts.

From the gusts? You don’t think it got any higher?

Roger Erickson: Well, yeah, it coulda been higher. When we go out and do tornado surveys, I see damage to whatever, there’s an app that I use to determine how strong the winds were to cause the damage that I’m looking at. So using that after a hurricane, you can do the same thing. Everything that I had was in the 140 to 150 range.

And that was about an hour before the eye got to shore?

Roger Erickson: About. Yeah. But the reality is it could have been 20 or 30 miles an hour more because if I know that the minimum requirement to damage this thing is 140, I know that it’s at least 140 but heck, it could’ve been 200 for all I know. But you can’t prove it. All I know is it’s for sure 140. You know what I’m saying? You’re stuck with whatever the lowest threshold to cause that damage that you’re looking at. So that’s the problem with after a tornado or after a hurricane — you look at the damage, you go, okay, well that’s 140-mile-an-hour, that’s 120-mile-an-hour. But in reality, it could’ve been 180 coming through here, but you don’t know that because there wasn’t anything strong enough to hold up 180 that would’ve shown it.

One-hundred and eighty an hour, the disaster passes, and then begins the war. Despite changes to the state’s legal policy in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina, insurance companies largely failed to pay policyholders their premiums within the mandatory 30-day timeframe after Hurricanes Laura and Delta. It took my mother over a year to get what she needed to fix our home.

Roger Erickson: I haven’t heard of anyone really having a good story. And after [Hurricane] Rita, I mean, most of us had an okay process getting our money from our insurance company.

I heard wonderful stories.

Roger Erickson: The only people that had a problem in Rita were the people closer to the coast because the insurance companies were arguing whether the damage to their houses was from the water or the wind. Because they’re like, if it’s from the water, we’re not gonna pay you that. So I mean, we had proof from that Cameron gauge that no, the wind happened first and then the water rose. So we were able to help the residents down there.

What came first — the wind or the water? It’s an ambiguous genesis, the facts of which nobody will ever know. But it matters — homeowners’ insurance and flood insurance are each separate policies — at any given time, you are only eligible to file a claim with one or the other, not both. If your homeowners’ insurance determines that the damage sustained was first caused by a flood, they have no obligation to you. The compensation you are entitled to also differs, depending on the policy that applies: Homeowners’ insurance pays the costs necessary to repair your house and temporarily relocate you, but FEMA’s flood insurance policy does not. It is only intended to reimburse you for the loss of your contents and the home’s damages. When it comes to finding someplace to live if your house is left uninhabitable, you are more or less on your own.

Angela Trahan: Well see FEMA right here, we ain’t get no money from ’em. They denied me because they said I was supposed to carry flood insurance. It’s a camper. You can’t carry flood insurance on a camper. So it didn’t matter that I was supposed to carry flood insurance from receiving assistance in a previous hurricane. And they denied me because of flood. It was a natural disaster. It was tidal water driven by hurricane force winds. And then I said, talk to the weatherman; I’m not a weatherman. But before the tidal wave got here, before the water even got here, there is no way mine was sitting here through the winds.

One million dollars

When the government doesn’t pay attention, people run around undeterred with their scams. I discovered one by accident while interviewing Rob Gaudet, who runs the Cajun Relief Foundation nonprofit. He listed at least four different groups that collect their own money separately from one another under variations of the Cajun Navy name, like gangs at war with one another. They each have their sovereign territory — when they cross into one another’s, one runs the other right back off.

He bragged to me that he raised a million dollars to provide aid and essential resources after Hurricanes Laura and Delta, the ice storm, and the flood. I was genuinely impressed by this. I drove out there to do more or less the same thing — pass out food and water and supplies to everybody — and could only gather a little over $1,000. The need was so great we had to turn people away. It’s the power of social media, he tells me. People love their brand.

He bragged to me that he raised a million dollars to provide aid and essential resources after Hurricanes Laura and Delta, the ice storm, and the flood…It’s the power of social media, he tells me. People love their brand.

And yes, they know that name. It is a funny inside joke. The “Cajun Navy” is a colloquialism that describes our neighbors who rescue one another in boats. I noticed something strange start to happen: When I called him for help, his group never showed up. He claims they did do work out there — they passed out thousands of meals, helped with muck and gut, tarped roofs, and hauled debris, which is what neighbors do for one another. He’s posted videos all year on Facebook, I guess, to prove it — to himself, to everybody else, and now, I assume, to me.

But I had doubts. He let it slip that he spent $200,000 of that one million dollars on real estate and between $60,000 and $70,000 fixing up the house he bought so that it’s something that he can eventually flip. The home was substantially damaged, he said; its previous owners just wanted out of it. His volunteers lived in it as they disaster-tourismed their way in and out of town while collecting a stipend. Meanwhile, the demand for livable housing after Hurricanes Laura and Delta was so great during Christmas of 2020 that a small tent community was set up by the lake. Of that one million dollars, he donated $10,000 to a different mutual aid group organizing housing relief five months after the first storm hit.

Gaudet then proceeds to sell me an elevator pitch of the disaster relief startup he wants to turn his nonprofit into so he can eventually sell it to the feds. I looked up his IRS records with his EIN. It turns out he failed to file the last few years, and in 2020, when the IRS revoked his tax-exempt status, he filed for 2016 four years late. So they reinstated it. I have the property records for the home.

Help us fund our next story

We’ve published hundreds of original stories, all funded by you — including personal essays, reported features, and reading lists.

In an attempt, I assume, to intimidate me, he mentions his friendship with Jeff Landry, Louisiana’s Attorney General — he says he calls him anytime anyone tries to accuse him of doing something wrong. He mentions his paranoia; that at one point he started to carry a gun.

I recorded him:

What have y’all been doing with donations that you have received?

Rob Gaudet: Donations are going to … we do pay some of our volunteers. They become team members to stay. Marissa has been there since December; she has her own life. Robin was there for three months. They’re away; they’re coming back. So, we pay our team members. I bought a house for these guys to live in. We bought some equipment, like a skid-steer. We bought a trailer for the skid-steer. We bought a tool trailer for all the tools we have. We bought tools. So, we’re building up our infrastructure with the donations that we have. And then we put people in hotel rooms. I gave $10,000 to Dominique and Roischetta during the ice storm for the people in the hotels.

For the Vessel Project. Yeah.

Rob Gaudet: Yeah. We bought heaters. We bought blankets. We buy stuff for people and we give it to them. We don’t really donate money directly to people usually. We will provide supplies to them, pick them up, and move them around. We’re just using it to cover our expenses while we’re in town.

Gotcha.

Rob Gaudet: And I will tell you, I raised a million dollars.

Wow. And that is specifically targeted towards Laura relief?

Rob Gaudet: Towards Laura, but some of it was for the ice storm. But mostly Laura and Delta.

[Was the house you purchased] damaged or was it in okay shape?

Rob Gaudet: It was damaged, it was damaged. The back side of the roof was lifted off.

So did y’all repair that home?

Rob Gaudet: Yes. It’s not fully repaired. It didn’t flood. Lake Street in front of our house flooded pretty badly, but it didn’t flood.

And how much did you buy it for?

Rob Gaudet: $200,000. The individuals wanted out of it. And the roof was really badly damaged so we had to have the roof repaired, put in new rafters, decking, re-roof the whole thing, re-shingle it, and then do the inside repairs. We’re pretty close to being done. It’s not quite done yet though.

After you’re finished with repairs, what is your plan for the house?

Rob Gaudet: We’re gonna sell it. Yeah, we’re gonna sell it. We’re pretty close to getting it on the market, actually.

How much will you sell it for?

Rob Gaudet: I think we’re going to ask $340,000. We’ve put some money into it. We’ve probably put $60,000 or $70,000 in repairs into it. Obviously you want to get as much for a house as you can. And that money goes back … it’s bought in the Cajun Navy nonprofit name and it all goes back to the nonprofit.

Habitat

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration suspended pollution monitoring and reporting mandates that companies were previously obligated to disclose to the agency. As a result, we won’t ever know the immediate environmental impact of Hurricane Laura because this order expired only a few days after the storm hit. The data just isn’t there. And there are so many parties with vested interests in covering up leaks and spills in that area: The Lake Charles economy is deeply dependent upon chemical refineries and oil rigs in the Gulf. But they could not hide the chlorine spill at BioLab after Hurricane Laura when it clouded I-10 West for several hours and forced it to shut down. Those who hadn’t evacuated were advised to shelter in place. There is a national chlorine shortage as a direct result.

The only reason industry rebuilds is to continue to produce rice, plastic, bleach, and oil. Lake Charles and Cameron are sacrificial land for these industries. I thought those towers and bright lights sparkling in the distance were New York growing up. That’s how many there are: Little cities pumping poison into the water we swallow, into the air we breathe. By the numbers, Southwest Louisiana hosts the majority of the state’s oil and gas refineries. The CITGO plant in Lake Charles processes 425,000 barrels of crude oil a day alone. The others manufacture a medley of harm: plastics, the chemical byproducts in shampoos, detergents, soaps, and bleach. It leaches into our waterways — there is so much.

There is no place left to swim. Warning signs are posted prominently at every lake and beach around the Gulf; when people ignore them, they get staph infections. The tap water in the town of Sulphur runs out the faucet brown.

Mr. Doxey: If it wasn’t for Venture Global I would not be down there right now. They would have shut the lights out of Cameron. That I can promise.

Oh yeah, the only reason they’re rebuilding Lake Charles is because of the plants. That’s the only reason they get any money.

Mr. Doxey: But if it wasn’t for them, I’m telling you, if this storm would’ve come two years before they started this plant.

Oh y’all would be gone.

Mr. Doxey: We wouldn’t even have electricity.

This environmental neglect is not new or unheard of — take, for example, the Chicot Aquifer and the Condea Vista spill in the ’90s. I can’t believe how well it’s been covered up. The company came in, poisoned the region’s main drinking aquifer with ethylene dichloride in one of the largest and longest-running chemical spills in our nation’s history, and just never disclosed it to those of us who live there. Between 19 and 47 million pounds of carcinogenic chemicals were siphoned into Lake Charles and its surrounding waterways through faulty pipelines. I drank the water from the tap growing up. There was no class action lawsuit or city-wide settlement. They poisoned us forever, and they never bothered to finish cleaning it up.

So tell me what happens when a hurricane comes and stirs all that muck and water up. What happens next when the same town is hit by a major disaster again? The water has to flood somewhere. And that’s just old chemical waste polluting our waterways through to the ground. There is no telling what else spilled in the Gulf afterwards that they won’t ever talk about. I’ve made my peace with the fact that we won’t ever know the chemical cocktail of waste they burned off into Lake Charles beforehand.

Just the other day, there was another industry explosion: Ethylene dichloride was implicated yet again.

Home

Why do we stay? I can’t give up on it. It is the birthplace of my culture and my home. We are the Cajuns, some of the last few left — first exiled from Acadia only a few hundred years ago in Le Grand Dérangement, when we refused colonization by the British. This is what brought us to Louisiana, this beautiful godforsaken wasteland. Y’all break my heart with this trying to run us off once again.

So y’all told me a little bit about how y’all’s neighbors are leaving and y’all’s plan is to stay no matter what.

Angela Trahan Doxey: Keep comin’ back.

Tell me how you make that decision?

Angela Trahan Doxey: I’m from here. Family land.

Victoria Trahan: My husband says that if daddy comes back, he comes back. And he always said if there’s a fence post on the property, I’m stayin’. So that’s what my husband goes by. And see this was my first time losing everything. When Rita hit, I was little. We went on vacation to Tennessee and all that. So I thought it was fun and when we came back things were having to be repaired. We didn’t know no better. Yeah we learned through it … you’re in school. But then this hit and we moved our camper out and a tornado got … and it still took … and we had to go pick up everything. And then my daughter is saying, [starts crying] “Mama, there’s my house.” The rest of it wasn’t coming back. I said it wasn’t. But I moved here four years ago and I made this a home, my kid’s home. So I came back. And I say if hurricane season hits again, I’m not coming back, but I know I’ll come back.

Angela Trahan Doxey: Born and raised here.

Carl James Trahan: We die here.

Victoria Trahan: And I say to my husband … when we first got together, I had a trailer in Lake Charles. He helped me move into it. It was gonna be mine. But I asked him, “Do you want to move in with me?” when we got serious and he [said], “You can’t take Cameron Parish outta me, baby, you just can’t.”

None of us own the earth. We just belong to it. This land is what makes us who we are.

None of us own the earth. We just belong to it. This land is what makes us who we are.

The light fades in Cameron, so I thank Angela and Carl and grab my things to go. I drive off into sunset with my left hand hanging out the driver-side window. I mean, what else can you say? We are losing all of this to the Gulf, to hurricanes, to pollution, to the government, to refineries, to climate change, to ignorance, and to willful neglect. I know it won’t look like this when I come back again. I drive off, and it’s as if I’m out of Sodom and Gomorrah. I look back and cry to salt.

So yeah, it is hell, and also, it is beautiful. I have never loved anything else like I love it. I watch the sky and its violent sunsets, when the chemicals bind together to make Technicolor gradients that dye the whole sky pink and red and white and yellow and blue and orange.

To visit Southwest Louisiana over the past year-and-a-half is to descend into hellish depths of human suffering. I do not know how else to put it. I have told everyone I know, tried to make them care, tried to hold those in positions of authority responsible for doing something about it, and had to reconcile the impossibility of manufacturing any grace for a part of the world that people do not regard kindly for whatever reason that they do. I don’t know why this is. It is a sociocultural landmine. The pirate Jean Lafitte buried treasure there. Except for Abbeville, I would never eat crawfish served anyplace else.

I am of that bit of earth. So I will not let it go. I show up in the small ways I can, which is talking to people, which is why I tell this to you.

***

Lauren Stroh is a writer from Louisiana. Other essays on hurricanes appear in Oxford American and n+1. Her criticism has been published by Art in America, Bookforum, Hyperallergic, The Nation, and many others.

***

Editor: Krista Stevens

Copy Editor: Cheri Lucas Rowlands

Fact checker: Julie Schwietert Collazo

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Get the Longreads Weekly Email

Get the Longreads Weekly Email